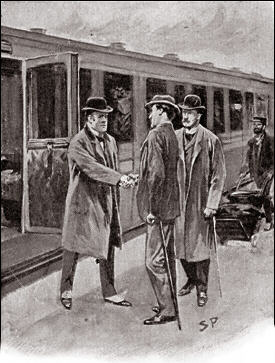

Sidney Paget's Strand Magazine illustration of Lestrade joining Holmes and Watson for The Hound of the Baskervilles

Sidney Paget's Strand Magazine illustration of Lestrade joining Holmes and Watson for The Hound of the Baskervilles

Dennis Hoey as Lestrade

Dennis Hoey as Lestrade

Colin Jeavons' Lestrade with Brett's Holmes

Colin Jeavons' Lestrade with Brett's Holmes

Eddie Marson to Robert Downey Jr.’s (equally unshaven) Holmes

Eddie Marson to Robert Downey Jr.’s (equally unshaven) Holmes

Aidin Quinn's Gregson in Elementary

Aidin Quinn's Gregson in Elementary

Quite a few Scotland Yarders take part in Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, the initial pattern set by the two in the first tale, A Study in Scarlet—rival Inspectors Gregson and Lestrade.

Described respectively as “a tall, white-faced, flaxen-haired man, with a notebook in his hand” and “a little sallow rat-faced, dark-eyed fellow, lean and ferret-like as ever,” they seek Holmes’s help, but don’t appear to think much of it (nor he of them): “Gregson is the smartest of the Scotland Yarders,” Holmes tells Watson. “He and Lestrade are the pick of a bad lot. They are both quick and energetic, but conventional—shockingly so.” Nor intend to give him credit for his help: “Supposing I unravel the whole matter, you may be sure that Gregson, Lestrade, and Co. will pocket all the credit.”

One wonders how actual Scotland Yarders of the day felt about it. (Athelney Jones in the next tale, The Sign of Four, was no different.) But Conan Doyle’s depiction of them was not without foundation. A principal source of his information about the outside world, when a young struggling doctor and writer in Southsea, Portsmouth, was the monthly periodical The Nineteenth Century, and in it he likely read, in May 1883, “Detective Police” by one Malcolm Ronald Laing Meason. Meason was born in 1824, served as an army officer until 1851, and then worked as a journalist in India, France, and England. This article, one of several such by Meason, contrasted Britain’s uniformed police’s efficiency at maintaining public order with the detective force’s pathetic inability at solving crimes. What was needed, Meason insisted, was deeper knowledge of crime, and the application of science. If young Dr. Conan Doyle needed convincing that Scotland Yarders weren’t up to snuff, Meason’s articles were surely the goods.

But in time Scotland Yard began to follow Meason’s advice, and Conan Doyle noticed. Whereas, in A Study in Scarlet, “Gregson and Lestrade had watched the maneuvers of their amateur companion with considerable curiosity and some contempt,” by 1902 The Hound of the Baskervilles struck a very different note when Lestrade entered the case: “A small, wiry bulldog of a man had sprung from a first-class carriage. We all three shook hands, and I saw at once from the reverential way in which Lestrade gazed at my companion that he had learned a good deal since the days when they had first worked together.” By 1904’s “Adventure of the Six Napoleons,” Lestrade had become positively fulsome: “I’ve seen you handle a good many cases, Mr. Holmes, but I don’t know that I ever knew a more workmanlike one than that,” he declares at its conclusion: “We’re not jealous of you at Scotland Yard. No, sir, we are very proud of you, and if you come down tomorrow, there’s not a man, from the oldest inspector to the youngest constable, who wouldn’t be glad to shake you by the hand.” He leaves Holmes momentarily touched.

A new generation of Scotland Yarders entered the stories as they continued, younger, better-educated men bringing more scientific method to crime detection. “Young Stanley Hopkins, a promising detective, in whose career Holmes had several times shown a very practical interest,” takes part in “The Golden Pince-Nez” and two other stories. Another, in 1915’s The Valley of Fear, is Inspector MacDonald, “a young but trusted member of the detective force, who had distinguished himself in several cases which had been entrusted to him. His tall, bony figure gave promise of exceptional physical strength, while his great cranium and deep-set, lustrous eyes spoke no less clearly of the keen intelligence which twinkled out from behind his bushy eyebrows.”

A farther cry from A Study in Scarlet’s Gregson and Lestrade can hardly be imagined. Scotland Yard had changed considerably since the 1880s, and Conan Doyle’s depiction of its detective officers changed with it.

In movies, Inspector Lestrade has dominated, the pattern there set by London-born actor Dennis Hoey, who played Lestrade as wiry bulldog—not brainy, but a faithful collaborator—in six of Basil Rathbone’s fourteen Sherlock Holmes movies between 1939 and 1946. Colin Jeavons undertook a more polished, clean-shaven Lestrade in Jeremy Brett’s 1980s television series, but Warner Bros’ recent Holmes movies have revived the rougher Lestrade, played by Eddie Marson to Robert Downey Jr.’s (equally unshaven) Holmes. Inspector Gregson and most of the Canon’s other Scotland Yarders have been under-represented in the dramatic arts, though in the current tv series Elementary, set in present-day New York City, Holmes’s principal police interlocutor is the quite up-to-date Inspector Gregson of the NYPD, played by veteran Irish-American actor Aidin Quinn.

--

Jon Lellenberg’s association with the Conan Doyle Estate stretches back to Dame Jean Conan Doyle’s time in the late 1970s. He is a Baker Street Irregular and a member of The Sherlock Holmes Society of London, and the author or co-author of five books about Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s life and work, including 2007’s award-winning Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters, done with Conan Doyle biographer Daniel Stashower and the Estate’s Charles Foley.