First depiction of the Irregulars in the first book edition of A Study in Scarlet, by Conan Doyle's own illustrator father Charles Altamont Doyle in 1889

First depiction of the Irregulars in the first book edition of A Study in Scarlet, by Conan Doyle's own illustrator father Charles Altamont Doyle in 1889

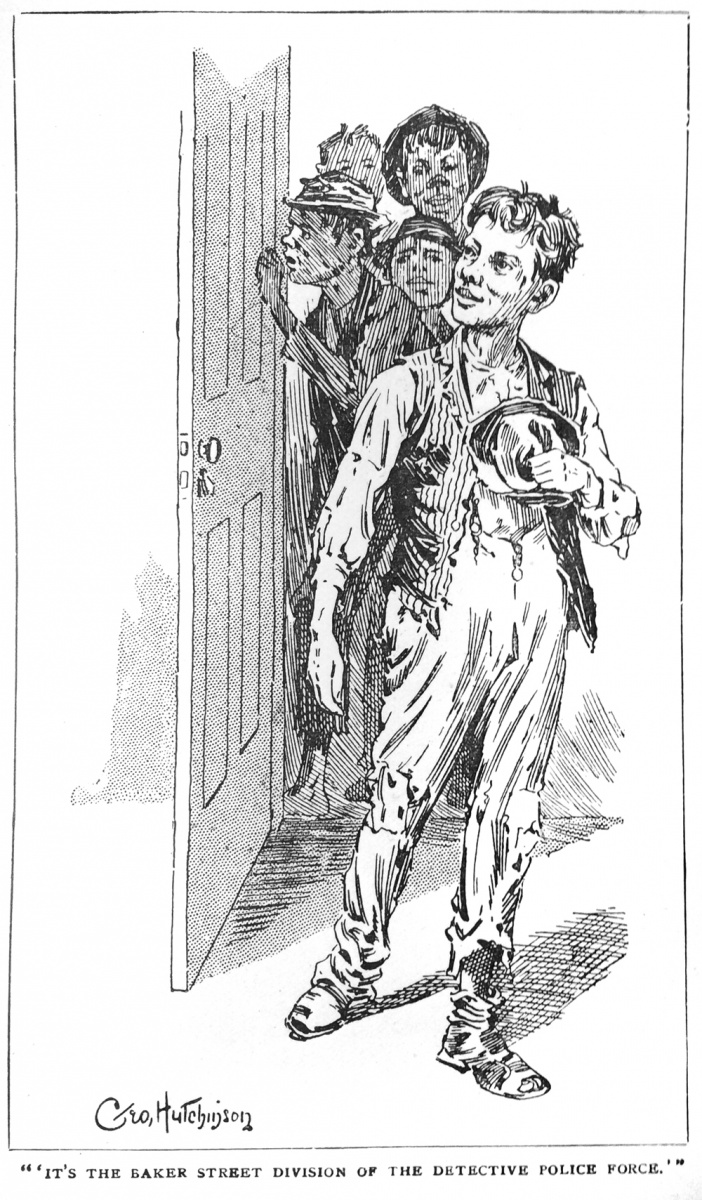

George Hutchinson's depiction of the Irregulars in the 1892 Ward, Lock edition of A Study in Scarlet.

George Hutchinson's depiction of the Irregulars in the 1892 Ward, Lock edition of A Study in Scarlet.

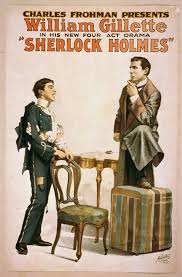

Billy the Page, with William Gillette's Sherlock Holmes, in the 1899 play of that name.

Billy the Page, with William Gillette's Sherlock Holmes, in the 1899 play of that name.

Billy the Page with Basil Rathbone in 1939's movie The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

Billy the Page with Basil Rathbone in 1939's movie The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

The Irregulars with Jeremy Brett's Sherlock Holmes (r.) and Edward Hardwicke's Dr. Watson.

The Irregulars with Jeremy Brett's Sherlock Holmes (r.) and Edward Hardwicke's Dr. Watson.

Like Irene Adler, Mycroft Holmes, and the deerstalker cap, the Baker Street Irregulars are an indelible part of Sherlock Holmes’s world that in fact make few appearances.

The Irregulars appear as bit players in just two adventures, helping Holmes track down the cabman Jefferson Hope in A Study in Scarlet,and searching out (without success) Jonathan Small’s getaway steam launch on the Thames River in The Sign of Four. That’s it. Technically, they also have a walk-on in 1893’s “The Adventure of the Crooked Man”—but only one of them, a “Baker Street boy” named Simpson who’s given but six words of dialogue confirming that he has located the fugitive Holmes is looking for.

Walk-ons, true; but so deftly described by Conan Doyle that the Irregulars have taken on iconic status. It’s not just that they fit into our classic picture of Victorian England—homeless ragamuffins living in squalor. For in a few strokes, Conan Doyle makes them fresh: no longer victims, or even adorable moppets, but allies in great adventures—street urchins as young professionals. They embody an essential part of Holmes himself: working undercover and without credit, but hired by a client who shows the respect due them within the constraints of a class-bound society. As ever, Conan Doyle is the master manipulator of stereotypes.

And per usual it was William Gillette, the first great dramatic and cinematic Sherlock Holmes, who provided the template for transferring the Irregulars onto stage and screen. Gillette took Holmes at his word: “in the future, they can report to you, Wiggins, and you to me,” Conan Doyle has Holmes say in The Sign of Four: “I cannot have the house invaded in this way.” For economic reasons, the Irregulars were impractical on the stage and unwieldy in film too, and were written out of silent film versions of A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four. Their group function, scouting for Holmes, could be compressed into the figure of a single kid.

And for a scout, Gillette didn’t bother with Wiggins in his 1899 play Sherlock Holmes: he had Billy the Page (hinted at in “The Crooked Man”), who became Gillette’s Wiggins in livery, an adoring but scrappy bellboy —Holmes’s domesticated street urchin. In Gillette’s play, Billy, “dressed as a street gamin and carrying a bunch of pink evening papers,” spies on Moriarty and his gang in front of Watson’s Kensington office. Gillette’s 1916 movie adaptation faithfully recorded the actual street scene: Billy watches Moriarty change places with a cabman, mingles with the gang in the street, then reports to Holmes, and so provides the fateful tip that leads to Moriarty’s arrest.

Silent film dramas followed suit in giving Billy all the necessary Irregular skills. In Denmark’s Nordisk series, Billy became a recurring character, blending street Arab with all-purpose servant and confidante. He replaced not only Wiggins but even Watson and Mrs. Hudson, who were all but erased from the series. And in the 1923 Eille Norwood version of “The Crooked Man,” Billy took over the function of “the Baker Street boy” in locating the elusive Henry Wood.

As best I can tell, the Irregulars have never appeared in movies, and with the arrival of talkies their metonyms Billy and Wiggins went into eclipse. Not until 1967, eighty years after their Canonical debut, did the Irregulars finally show up on the screen—not the big one, but TV’s. Pride of place goes to the BBC’s version of A Study in Scarlet starring Peter Cushing, that presented a trimmed, four-boy version of the Irregulars in a brief scene at Baker Street. Not until the 1980s did the Irregular industry shift into high gear, starting with the BBC deciding to give the Irregulars a series of their own, The Baker Street Boys, a league of loveable street-wise teens (four boys, two girls) who work on their own. Then in 1987 the Irregulars were at last presented in their Canonical glory. Granada’s elegant version of The Sign of Four starring Jeremy Brett portrayed Holmes’s invisible army in loving detail: a noisy rabble who invade the Baker Street sitting-room and who, hired to hunt for the launch Aurora in The Sign of Four, literally cover the waterfront, and this time actually find it.

Since then variants of the Irregulars have come into their own. Sherlock Holmes and the Baker Street Irregulars was a one-off TV feature for children in 2007 with Jonathan Pryce as Holmes. Perhaps the most ingenious twist so far came in the BBC’s Sherlock series starring Benedict Cumberbatch, in its “The Empty Hearse” episode: an homage to online fans where buffs collaborate to solve the mystery of Holmes’s survival—even creating a Google Street Map that allows them to “go everywhere, see everything” unobserved: Irregulars as couch potatoes, including a goth teenage girl. And when the mystery is finally explained, one of them remarks: “Not the way I’d have done it.” As ever, Holmes has the last word: “Everyone’s a critic.” Even, it appears, the updated Baker Street Irregulars.

--

Russell Merritt, a longtime member of The Baker Street Irregulars (the American Sherlock Holmes society), is professor of film at the University of California at Berkeley. Born in New Jersey, raised in Connecticut, and educated at Harvard, Professor Merritt recently participated in the restoration of William Gillette’s rediscovered 1916 Sherlock Holmes movie, and Richard Oswald’s 1929 Der Hund von Baskerville.