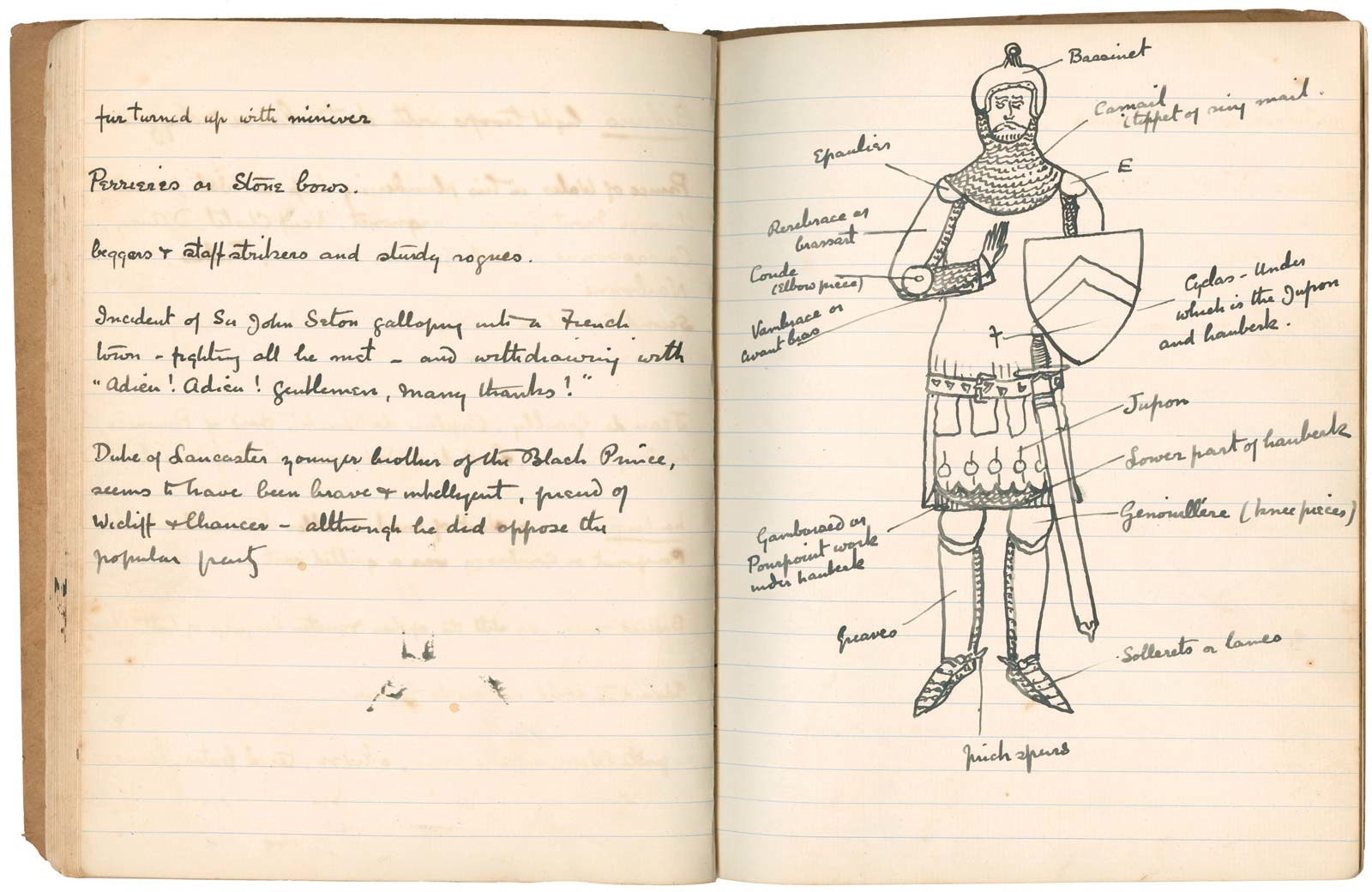

A page from Conan Doyle's research notebook for The White Company, now in the C. Frederick Kittle Collection of Doyleana at Chicago's Newberry Library.

A page from Conan Doyle's research notebook for The White Company, now in the C. Frederick Kittle Collection of Doyleana at Chicago's Newberry Library.

The Classics Illustrated edition from 1952, presenting the story for adolescents.

The Classics Illustrated edition from 1952, presenting the story for adolescents.

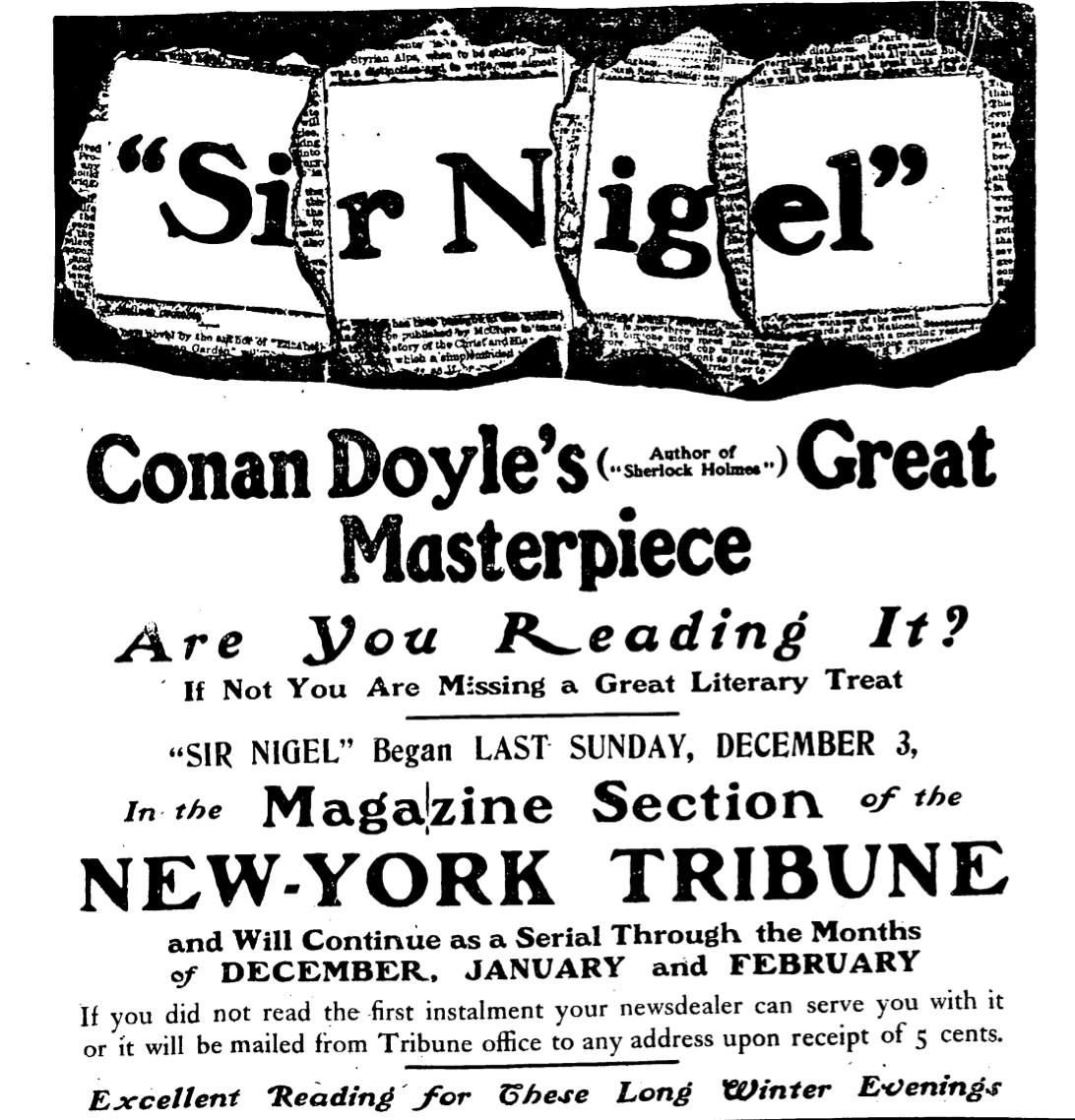

In 1905 and 1906, the New York Tribune newspaper paid a then-whopping $25,000 for the serialization rights to Sir Nigel, running this ad for it in its December 8, 1905 issue.

In 1905 and 1906, the New York Tribune newspaper paid a then-whopping $25,000 for the serialization rights to Sir Nigel, running this ad for it in its December 8, 1905 issue.

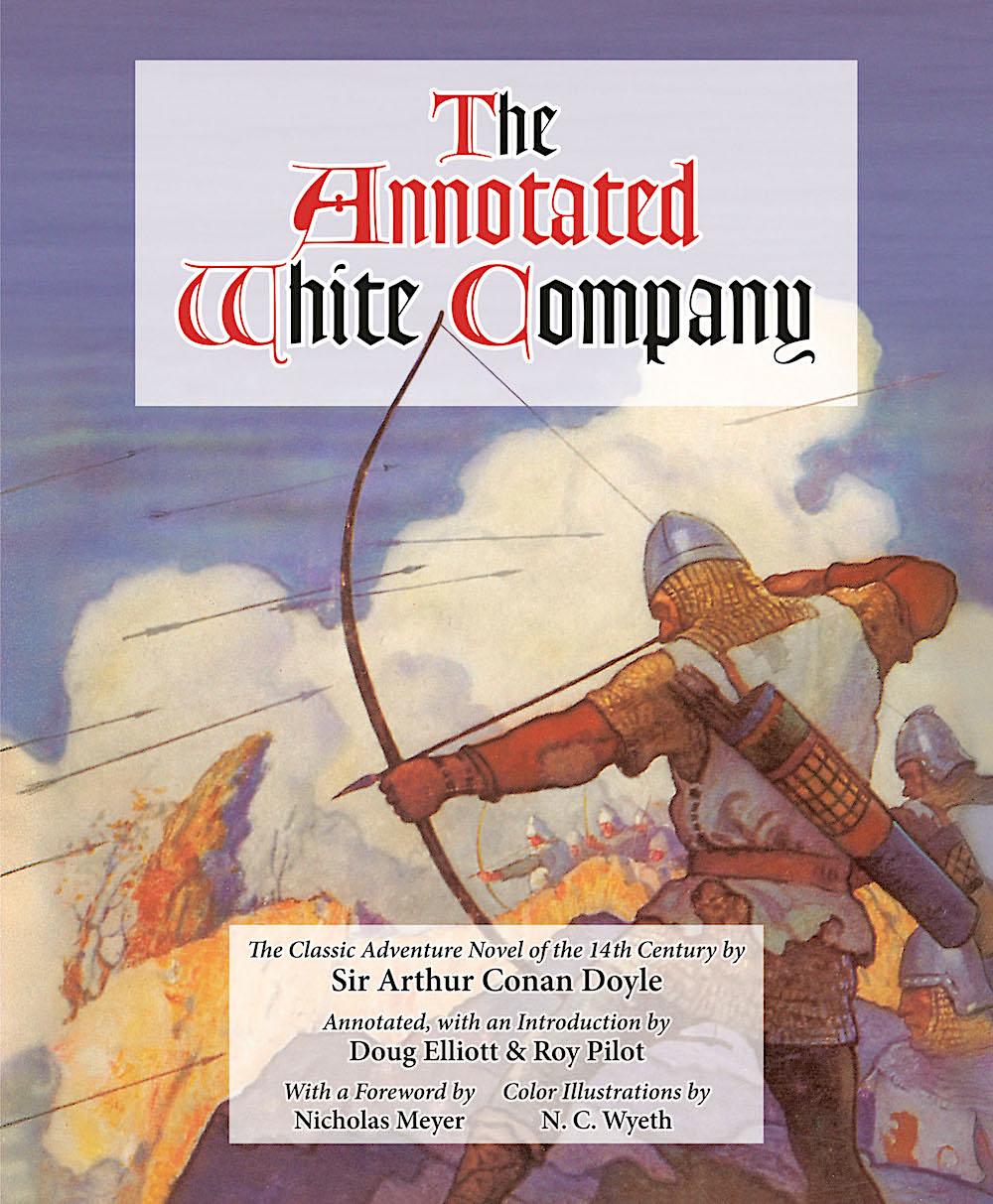

Newly published in January 2020, a thoroughly annotated edition of The White Company by two well-known Conan Doyle scholars from Wessex Press of Bloomington, Indiana, with a foreword by Hollywood writer and director Nicholas Meyer.

Newly published in January 2020, a thoroughly annotated edition of The White Company by two well-known Conan Doyle scholars from Wessex Press of Bloomington, Indiana, with a foreword by Hollywood writer and director Nicholas Meyer.

Sir Nigel was a slight man of poor stature, with soft lisping voice and gentle ways. So short was he that his wife, who was no very tall woman, had the better of him by the breadth of three fingers.

Arthur Conan Doyle consistently maintained that The White Company (1891) and its prequel Sir Nigel (1906) were his most important works of fiction.

The two novels—both featuring that chivalric paragon, Sir Nigel Loring—were particularly dear to his heart because in them he hoped to emulate and surpass Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and Charles Reade’s The Cloister and the Hearth, both of which he fervently admired. While those two medieval romances are too seldom read nowadays, Conan Doyle’s own masterly re-creations of 14th-century England and France remind us, yet again, how rich, varied and rewarding his non-Sherlockian books can be.

To write The White Company and Sir Nigel, Conan Doyle immersed himself for months in study, absorbing memoirs and chronicles, as well as entire shelves of the latest medieval and military histories. Today we sometimes label the period he was researching “the calamitous 14th century,” when the Black Death ravaged Europe, conflict between France and England would be designated The Hundred Years War, and the feudal order, the Catholic Church, and knightly ideals began to be questioned and renounced.

And yet this same age, in Conan Doyle’s view, stood for patriotic and personal virtues we forget to our peril. It’s hardly happenstance that a man who actually lived by the pen, not by the sword, should lie beneath a gravestone inscribed “Steel True, Blade Straight.” For Sir Arthur as for Sir Nigel, chivalry was grounded in duty, honor, tradition, loyalty, physical prowess and good sportsmanship, courtesy, charity, piety, service, and love of family. These, he insisted, characterize a moral, civic, and martial tradition worth honoring and living up to even in the modern world.

Sir Nigel Loring wholly embodies these ideals. We first meet him in The White Company, as he takes command of this so-named cadre of English archers and men-at-arms. He is 46 years old and already famous, though in looks hardly a Prince Valiant:

Sir Nigel was a slight man of poor stature, with soft lisping voice and gentle ways. So short was he that his wife, who was no very tall woman, had the better of him by the breadth of three fingers. His sight having been injured in his early wars by a basketful of lime which had been emptied over him when he led the Earl of Derby’s stormers up the breach at Bergerac, he had contracted something of a stoop, with a blinking, peering expression of face.

To drive home how unprepossessing this hero is in appearance, Conan Doyle compares his features with those of his wife Lady Mary:

certes, had the two visages alone been seen, and the stranger been asked which were the more likely to belong to the bold warrior whose name was loved by the roughest soldiers of Europe, he had assuredly selected the lady’s. Her face was square and strong, with thick brows, and the eyes of one who was accustomed to rule. Taller and broader than her husband, her flowing gown of sendal and fur-lined tippet, could not conceal the full outlines of her figure. It was the age of martial women.

Sir Nigel not only adores his stout, rather fearsome wife, he is also putty in the hands of their beautiful daughter Maude.

What’s more, Conan Doyle invests him with some of the loveable absurdity of Don Quixote, especially in his unflagging zeal to advance himself in honor and renown through challenges and hand-to-hand combat. Though a formidable warrior, when writing to Lady Mary he produces a single run-on sentence, largely about recent battles and skirmishes, as he circles around saying that he loves and misses her.

When The White Company and Sir Nigel first appeared, they were favorably reviewed, to their author’s irritation, as boys’ adventure stories. They have never quite shaken that association. Yet any reader soon recognizes that Conan Doyle takes pains to present the full Chaucerian range of medieval types: Kings, princes, nobles, peasants, monks, brigands, con artists, innkeepers, huntsmen, nuns, wenches, sailors, poets, and pilgrims. Some are good, many are rascals or worse. In both novels aristocratic landowners and the Catholic clergy are shown to be venal and corrupt. The poor are driven to robbery and murder through hunger and abuse by their overlords. Had the lines not already been taken, Conan Doyle might well have started his novel: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

While The White Company takes up Sir Nigel at the height of his fame, it mainly focuses on his squire, the monastery-educated Alleyne Edricson. A second son without property, Alleyne nonetheless hopes that on the battlefield he can win the respect of Sir Nigel and the hand of the beautiful Maude. (Needless to say, he does.)

When Conan Doyle returned to the 14th century in 1906 with Sir Nigel, he decided to relate what we would now call his hero’s origin story, tracking how an impoverished, almost landless scion of an ancient family earned his knighthood. Brought up by his grandmother to be faithful to the already slightly old-fashioned style of chivalry espoused by his late father and grandfather, young Nigel defies rapacious monks who threaten to seize what little property has been left to his family, then further demonstrates his mettle by taming a reputedly untamable yellow horse, thus acquiring his fierce battle steed Pommers.

During the wars young Nigel—squire to the real-life knight Sir John Chandos—vows to perform three acts of valor to win the hand of his beloved Mary. He eventually hunts down a spy known as the Red Ferret; daringly rescues 20 archers held captive by a brutal warlord; and, most amazingly, takes a most unexpected prisoner at the battle of Poictiers. In several ways, Sir Nigel is a better book than its predecessor—faster-paced, with more variety in its action and fewer tableaux-like descriptions. While the older Sir Nigel can seem foolish or even half-deluded in his quest for glory, his younger self starts off hotheaded, but gradually learns that the specific virtue of the warrior-hero is self-control.

While Conan Doyle especially shines in his battle scenes, both The White Company and Sir Nigel shouldn’t be rushed through. Lyrical passages, elaborate descriptions, catalogues of knights, period diction, and technical terms involving armor and weaponry—all are used to summon up the color and pageantry of a distant age. The secondary characters in both books can sometimes be types, but many of Sir Nigel’s companions are, like Chandos, actual historical figures, notably Edward III, his son The Black Prince, and the ultra-rational commando leader Sir Robert Knolles, as well as that great French champion Bertrand de Guesclin, and his stately, clairvoyant wife Lady Tiphaine.

It’s said the blustery Professor George Edward Challenger was Conan Doyle’s favorite among his characters. Certainly the world’s favorite is Sherlock Holmes, the noted consulting detective. Yet neither of these comes close to Sir Nigel Loring in representing Conan Doyle’s own ideal of what it means to possess nobility of heart and greatness of soul. It seems only fitting that when a latter-day warrior, General and President Dwight D. Eisenhower, lay dying, a copy of Sir Nigel rested upon his nightstand.

--

Michael Dirda is an ink-stained wretch who has long contributed a weekly book column to the Washington Post. His own books include the 2012 Edgar Award-winning On Conan Doyle: Or, the Whole Art of Storytelling, the memoir An Open Book, and five collections of essays: Readings, Bound to Please, Classics for Pleasure, Book by Book, and Browsings. His current project, tentatively titled The Great Age of Storytelling, focuses on the birth of modern genre literature in late 19th- and early 20th-century Britain. Dirda holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Cornell and is “Langdale Pike” in The Baker Street Irregulars. He received the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for Distinguished Criticism.