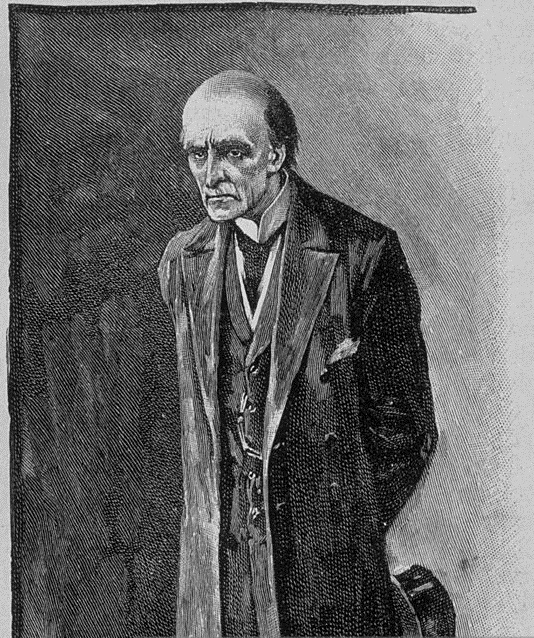

Sidney Paget's portrait of Professor Moriarty for the December 1893 Strand Magazine.

Sidney Paget's portrait of Professor Moriarty for the December 1893 Strand Magazine.

Gustav von Seyffertitz's halloweenish Moriarty in John Barrymore's 1992 movie Sherlock Holmes.

Gustav von Seyffertitz's halloweenish Moriarty in John Barrymore's 1992 movie Sherlock Holmes.

Ernest Torrance's thuggish Moriarty in Clive Brook's 1932 version of Sherlock Holmes.

Ernest Torrance's thuggish Moriarty in Clive Brook's 1932 version of Sherlock Holmes.

Henry Daniell, left, one of three Moriarty's in Basil Rathbone's Sherlock Holmes movies.

Henry Daniell, left, one of three Moriarty's in Basil Rathbone's Sherlock Holmes movies.

Sir Laurence Olivier as a sinister but misunderstood Moriarty in 1976's The Seven-Per-Cent Solution.

Sir Laurence Olivier as a sinister but misunderstood Moriarty in 1976's The Seven-Per-Cent Solution.

Eric Porter as probably the most faithful portrayal of Moriarty, in the Jeremy Brett television series in the 1980s.

Eric Porter as probably the most faithful portrayal of Moriarty, in the Jeremy Brett television series in the 1980s.

“He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson,” says Sherlock Holmes of Professor James Moriarty, the celebrated Binomial Theorem expert and author of The Dynamics of an Asteroid.

One of the first brains of Europe, with all the powers of darkness at his back, he sits, motionless, like a spider in the center of his web, in control of the deep organizing power forever standing in the way of the law—the only man the great detective considers his intellectual equal. Although he appears in only two tales directly, “The Final Problem” and The Valley of Fear (if alluded to in five others), his presence permeates the Canon’s four novels and 56 short stories in a way no other character does, save for Holmes and Watson themselves.

Just as the ghost of Baron Scarpia overshadows the lives of the doomed lovers in Puccini’s Tosca, so the malignant shade of Moriarty stalks the entirety of the Canon. Although the tales were written out of chronological sequence, with the climactic battle between Holmes and his arch-nemesis arriving roughly midway, the genius of the Amanuensis was such that, practically from the start, we sense, rather than see, Moriarty, and dread his inevitable arrival. Yet even after he’s subsequently dispatched by Holmes with a cunning baritsu maneuver at the Reichenbach Falls, his menace lives on.

The name, like Doyle’s, is Irish: Ó Muircheartaigh, a County Kerry name translating roughly as “skilled navigator.” The family blazon is variously described, including “An arm embowed the hand grasping a sword with a snake entwined about the blade all proper the arm charged with a fleur-de-lis.” The snake is a nice touch.

As noted in “Moriarty, Moran, and More: Anti-Hibernian Sentiment in the Canon,” one of my two contributions to Sherlock Holmes in America (Skyhorse, 2009), the significance of the name goes beyond mere paddywhackery; for Conan Doyle, the prefix “mor” is, throughout the Canon, inextricably bound up with death. Not only Moriarty and his wicked henchman Colonel Sebastian Moran, but Watson’s lovely bride Mary Morstan as well, are destined for untimely fates; hence we learn of Mary’s untimely demise in, significantly, the Sherlockian resurrection tale “The Empty House,” which therefore has a double meaning of resonance: “Without Watson’s sad bereavement, there can be no Return of Sherlock Holmes. In order for Holmes to live again, Mary must trade places with him . . . . giv[ing] up her husband and return[ing] Watson to the embrace of Sherlock Holmes, Mrs. Hudson, and Baker Street.”

But though gone as well, Moriarty lives on. Beyond his starring role in “Final Problem” and off-stage cameo in Valley of Fear (a tale that is the most explicit example of Conan Doyle’s Irish Catholic self-rejection, with its parade of Irish-American villains), his baleful shade hovers over the remainder of the Canon, like Marx’s specter (and James Bond’s SPECTRE; one can argue that Moriarty is the first Bond villain) haunting Europe and the rest of the civilized world. The comparison is apt: from Moriarty to Marx to Ernst Stavro Blofeld, the procession of supervillains who want to rule and ruin the world is linear, and immutable.

The mercy of Holmes, a parfit gentil knight, is never strained, no matter whom his adversary: in “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange,” Holmes arbitrarily frees Jack Croker, the killer of Sir Eustace Brackenstall, by appealing to Watson’s innately British rectitude and sense of justice: “Once or twice in my career I feel that I have done more real harm by my discovery of the criminal than ever he had done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience.”

But not so with Moriarty. A figure of implacable evil, he occupied so much space in his creator’s imagination that Conan Doyle doubled down on his character, even giving the Professor’s brother, a retired army colonel, the same first name, James—perhaps subconsciously conflating him with yet another Angel of Death, Colonel Moran. And yet, physically, Moriarty is unprepossessing: tall but balding and (in Sidney Paget’s portrait) slender to the point of cadaverous: as is, please note, Holmes himself, although the detective’s vitality is the antithesis of Moriarty’s lugubriousness. Equally matched, both intellectually and physically, in “The Final Problem” the two doppelgängers wrestle, then vanish in the mists.

In the Canon’s latest-set story, “His Last Bow” in 1914 on the eve of the Great War, written in the third person omniscient, Holmes stands with Watson peering into the Moriartian future:

“There’s an east wind coming, Watson.”

“I think not, Holmes. It is very warm.”

“Good old Watson! You are the one fixed point in a changing age. There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it's God’s own wind none the less, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.”

There speaks the Holmes the optimist. Having vanquished Moriarty in Switzerland, the aging consulting detective (b. January 6, 1854?) addresses the greatest catastrophe in European history with an equanimity we might today find unnerving. For we have seen this movie, and know how it ends: the east wind birthed by Moriarty, and blown across the Channel by Bismarck and Kaiser Bill, turns into the tornado of Nazism, which in turn will give way to the arctic chill of Cold War, and, today, Europe’s uncertain demographic and political future. And so we arrive at the final problem: the Moriartys, the Morans, yea even the Morstans, are always on the perimeter of the safe haven of 221B—if, as in “The Empty House,” sometimes dangerously nearby—yet are ever present at the center of the Holmesian moral universe.

In fact, they are vital to it. Moriarty could very well have lived without Sherlock Holmes. But Sherlock Holmes could not have lived without Professor Moriarty.

--

Michael Walsh, a graduate of the Eastman School of Music, was Time Magazine’s longtime music critic, and now divides his writing time between Lakeville, Conn., and his ancestral home in County Clare, Ireland. A prolific writer of both fiction and nonfiction, his 2003 novel And All the Saints is an award-winning portrait of New York City’s own Professor Moriarty, 1920s Prohibition-era mob boss Owney Madden. Mr. Walsh’s other books and screenplays range over the worlds of music and theater, cultural-political commentary, and several modern-day spy thrillers.