Wallace Beery as the first dramatized Professor Challenger, 1922.

Wallace Beery as the first dramatized Professor Challenger, 1922.

Conan Doyle in disguise as Professor Challenger.

Conan Doyle in disguise as Professor Challenger.

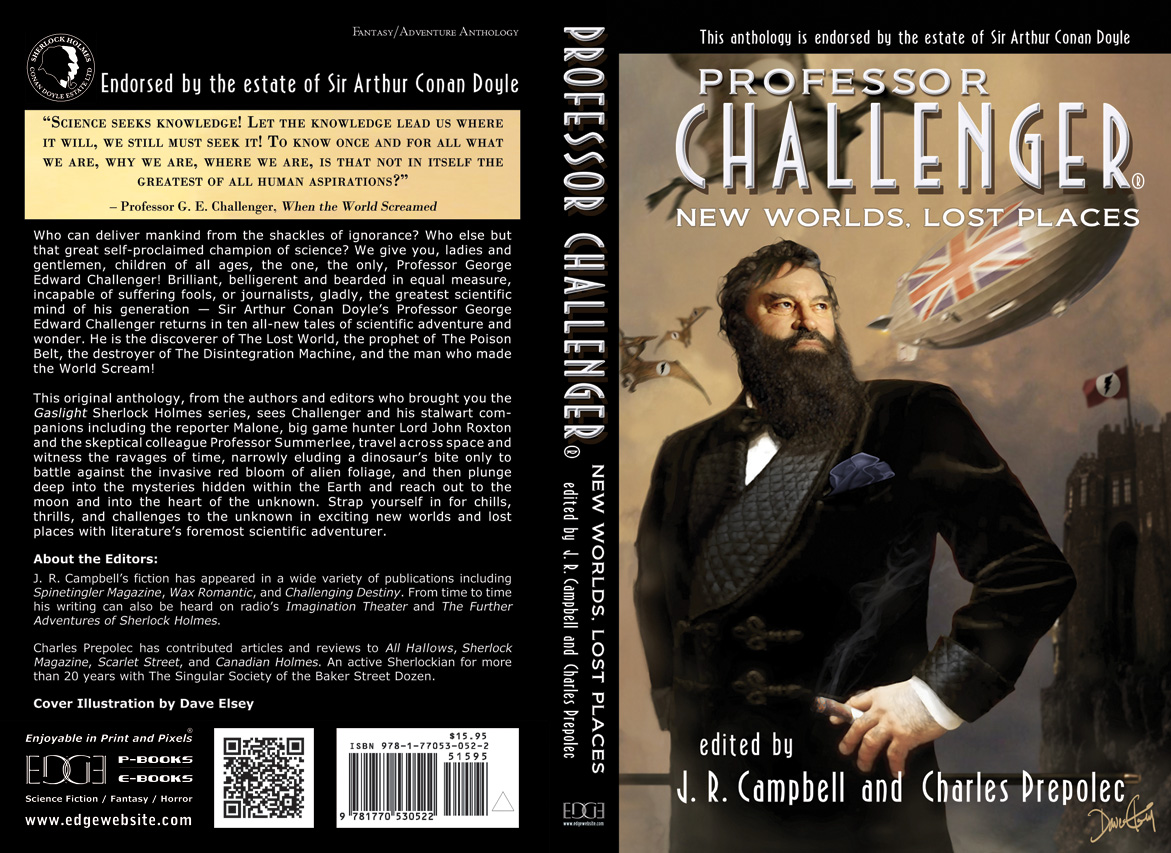

The most recent revival of Professor Challenger in print.

The most recent revival of Professor Challenger in print.

There is no evidence that Challenger is actually a professor, teaching students whether eager or intimidated. He is an independent scholar, as we now say, supported in his research by a series of inventions, and later by a rubber millionaire who leaves Challenger his fortune for the pursuit of science.

George Challenger, physician and scientist, was introduced in the April 1912 Strand Magazine where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Lost World was serialized.

Our first impression of Challenger — apart from learning that he’d broken the skull of a reporter from the Telegraph — is a summary of his professional achievements, read to anxious London Gazette reporter Ned Malone by his editor:

‘Challenger, George Edward. Born: Largs, N. B., 1863. Educ.: Largs Academy; Edinburgh University. British Museum Assistant, 1892. Assistant-Keeper of Comparative Anthropology Department, 1893. Resigned after acrimonious correspondence same year. Winner of Crayston Medal for Zoological Research. Foreign Member of’ — well, quite a lot of things, about two inches of small type —‘Societe Belge, American Academy of Sciences, La Plata, etc., etc. Ex-President Palaeontological Society. Section H, British Association’ — so on, so on! —‘Publications: “Some Observations Upon a Series of Kalmuck Skulls”; “Outlines of Vertebrate Evolution”; and numerous papers, including “The underlying fallacy of Weissmannism,” which caused heated discussion at the Zoological Congress of Vienna. Recreations: Walking, Alpine climbing. Address: Enmore Park, Kensington, W.’

And we soon learn that Challenger possesses, in entertainingly exaggerated degree, all the stereotypical traits of the dogmatic academic: irascible, combative, aggressively self-assured, and antisocial.

Yet there is no evidence that Challenger is actually a professor, teaching students whether eager or intimidated. He is an independent scholar, as we now say, supported in his research by a series of inventions, and later by a rubber millionaire who leaves Challenger his fortune for the pursuit of science. Indeed, as a professional iconoclast it would have been difficult for Challenger to navigate the often nasty, if petty, politics of academic life, and his Professorship seems to have been purely honorary.

Worse yet, Challenger’s physical appearance suggests nothing so much as a huge, hairy ape, as Malone describes:

It was his size which took one’s breath away — his size and his imposing presence. His head was enormous, the largest I have ever seen upon a human being. I am sure that his top-hat, had I ever ventured to don it, would have slipped over me entirely and rested on my shoulders. He had the face and beard which I associate with an Assyrian bull; the former florid, the latter so black as almost to have a suspicion of blue, spade-shaped and rippling down over his chest. The hair was peculiar, plastered down in front in a long, curving wisp over his massive forehead. The eyes were blue-gray under great black tufts, very clear, very critical, and very masterful. A huge spread of shoulders and a chest like a barrel were the other parts of him which appeared above the table, save for two enormous hands covered with long black hair. This and a bellowing, roaring, rumbling voice made up my first impression of the notorious Professor Challenger.

Yet despite this inauspicious introduction, Challenger ultimately emerges as a sympathetic character, a favorite of his creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and one his daughter Dame Jean called “strangely endearing.” Challenger displays a tender streak early on in The Lost World through his love for his wife, and in affections later revealed more fully in his concern for his companions in exploration — including, in a sequel to The Lost World, his heroic efforts to save them from the “Poison Belt” he believed threatening all life on earth. In Challenger, as with Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle displayed his genius for drawing compelling, complex figures whose distinctive flaws and faults are counterbalanced by endearing and admirable qualities, becoming heroic by overcoming those flaws and succeeding despite those faults.

And it helps that Challenger takes obvious delight in his own cantankerous antics, a wink at readers who are invited to play along. In The Lost World, Challenger’s belief that dinosaurs survive on a remote plateau in South America is ridiculed by his colleagues in London. One of them, Professor Summerlee, leads an expedition to South America to test Challenger’s claim. Challenger joins the expedition, which locates the plateau, does encounter living dinosaurs, and after a series of adventures returns to London to report the discovery. When his critics remain skeptical, Challenger unleashes a baby pterodactyl in the Queen’s Hall that panics the assembled Zoological Institute. He is vindicated, though the pterodactyl escapes and Ned Malone loses the girl he’d intended to impress by taking part in the expedition.

Conan Doyle’s Lost World adventure story drew inspiration from sources ranging from the literary, such as H. Rider Haggard’s novels, to the nonfictional exploits of the explorer Percy Fawcett, as well as the mania for fossils and fossil-hunting that griped gentlemen-scientists and bone-hunters (including Conan Doyle) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Challenger was modeled in large part on Edinburgh University’s William Rutherford, who Sir Arthur had known when a medical student (calling Rutherford “a ruthless vivisector” in his autobiography Memories and Adventures); and whose “peculiarities,” including physical appearance, Conan Doyle incorporated into his fictional Challenger, whose barrel chest, huge head, and Assyrian beard were, Conan Doyle later wrote, taken directly from Rutherford.

It also seems likely that Sir Arthur recalled Sir Charles Wyville Thompson, Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh from 1870. In 1876, just a few months before Conan Doyle began his studies at that university, Thompson had returned from a well-publicized three-year, round-the-world voyage of exploration and collecting — on the ship HMS Challenger. But other scientists known to Conan Doyle have also been proposed as models, and it may be simply that Conan Doyle intended Challenger to embody a range of stereotypical features of scientists and academics of the day. All the possibilities have been ably explored in The Annotated Lost World (1996) by Alvin E. Rodin M.D. and Roy Pilot.

Apart from these models and inspirations, Professor Challenger was also an alter-ego for Conan Doyle, a figure through whom the author could indulge his passion for science, travel, and invention while allowing Challenger to be unhindered by the conventions of polite society. He described Challenger as “a character who has always amused me more than any other which I have invented.” In fact Conan Doyle disguised himself as Professor Challenger for a series of photos used in the book publication of The Lost World, relishing the charade.

Conan Doyle returned to Professor Challenger in two more novels, The Poison Belt (1913) and The Land of Mist (1926), and two short stories, “When the World Screamed” (1928) and “The Disintegration Machine” (1929). The Land of Mist opens with Challenger’s forceful rejection of Spiritualism, but he is ultimately converted to the reality of the spirit world, a cause for which Conan Doyle was active in the 1920s. The Lost World has never been out of print, and has inspired movies, TV shows, and radio adaptations. For the first movie version, a silent released in 1925, the need to create life-like dinosaurs led movie director Willis O’Brien to new heights of technical perfection with stop-motion prehistoric creatures that would lead to his King Kong in 1933 as well. In 1922, Conan Doyle brought early Lost World footage to a meeting of the Society of American Magicians, in order to astonish men who’d been trying to debunk his beliefs in Spiritualism. Upon release in February 1925, the movie, starring Wallace Beery, was an immediate hit, and became the first in-flight movie entertainment in history, on an Imperial Airway flight from London to Paris that April.

At least six additional movie versions of the novel have been produced, and two TV series. A number of other writers have been inspired by The Lost World to create their own versions of the classic story, including Tarzan-creator Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1916 The Land That Time Forgot, and Michael Crichton’s 1990 Jurassic Park and 1995 The Lost World. The combination of adventure, a lost world, and, of course, the irascibly loveable Professor Challenger, continues to entertain and inspire more than 100 years later.

--

Written by Professor Donald K. Pollock, who like Professor Challenger, trained in both medicine and anthropology. He is Chair of the Department of Anthropology at SUNY/Buffalo, Director of the program in Medical Anthropology, and Adjunct Professor of Geographic Medicine. And like Professor Challenger, he has traveled extensively in the Amazon, most notably for several years' research among the Kulina Indians of Western Brazil, where, sadly, he discovered no dinosaurs. He lives in Niagara Falls, New York.

-28112018163643.png)