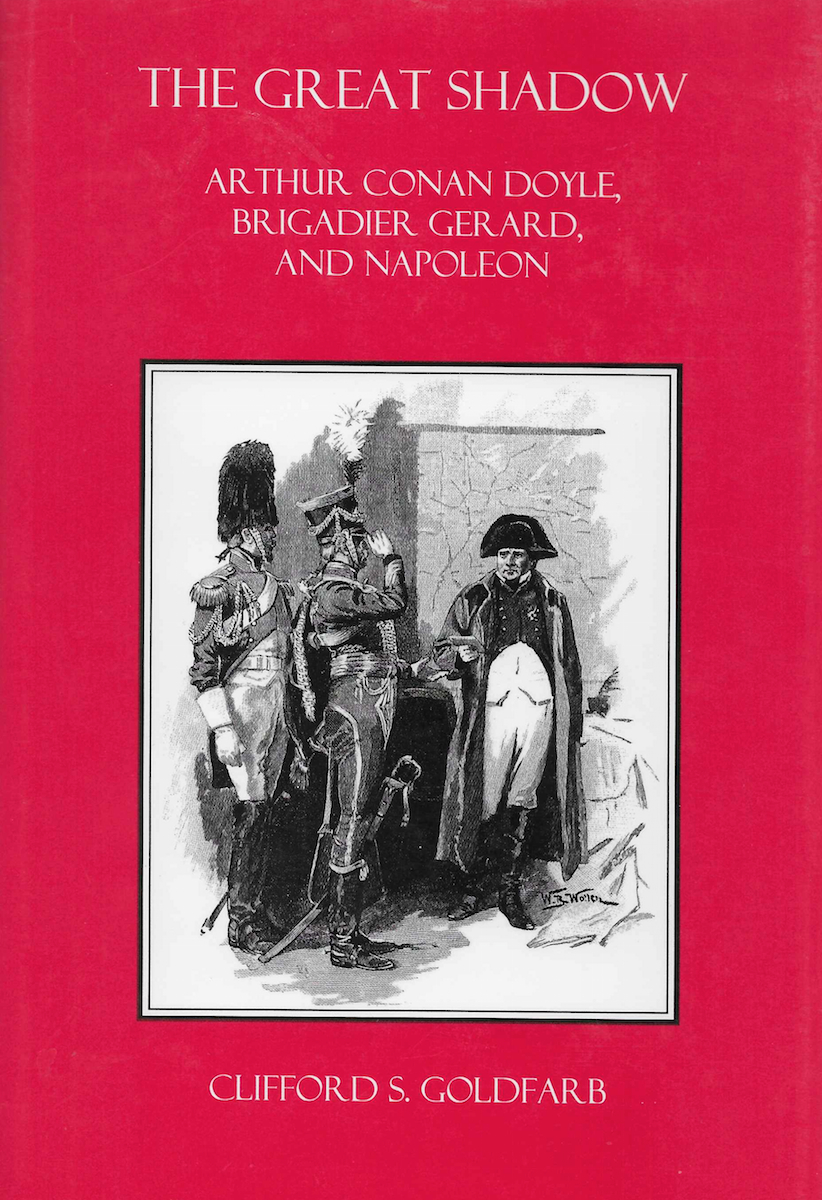

Napoleon as he appears on the cover and on the inside of Goldfarb's 'The Great Shadow'

Napoleon as he appears on the cover and on the inside of Goldfarb's 'The Great Shadow'

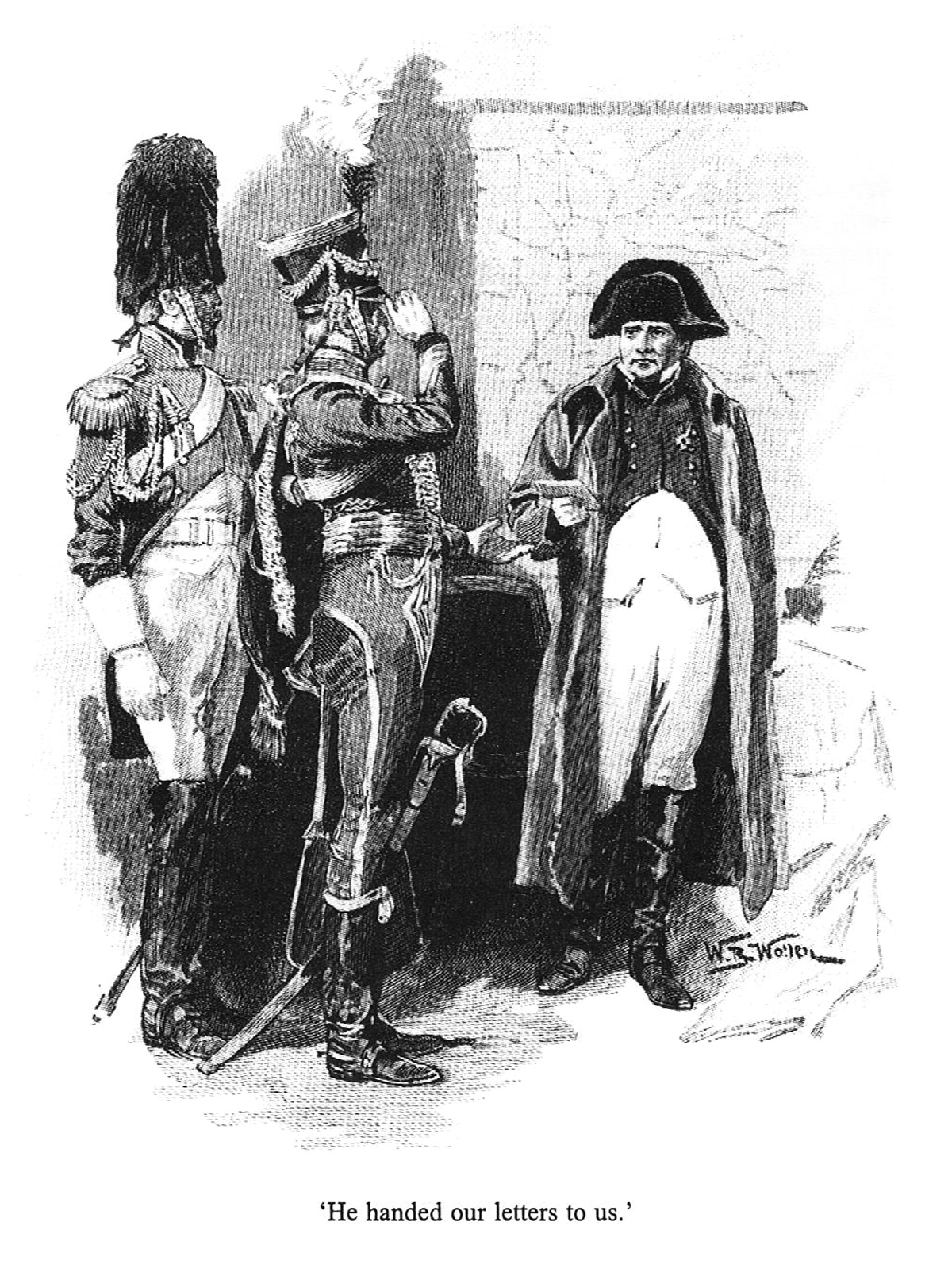

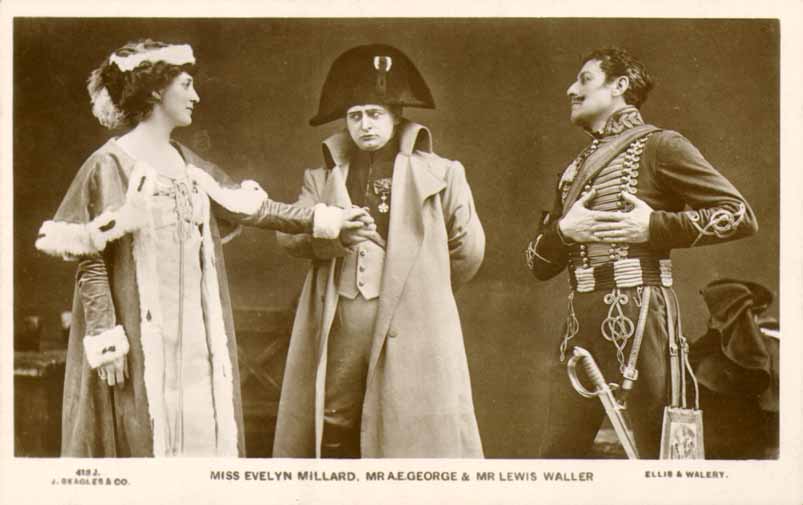

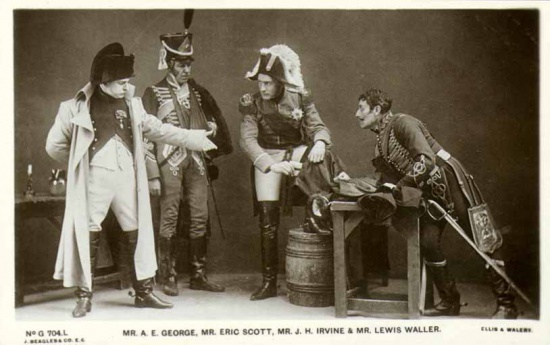

From the 1906 stage play written by Arthur Conan Doyle

From the 1906 stage play written by Arthur Conan Doyle

From the 1906 stage play written by Arthur Conan Doyle

From the 1906 stage play written by Arthur Conan Doyle

From the 1906 stage play written by Arthur Conan Doyle

From the 1906 stage play written by Arthur Conan Doyle

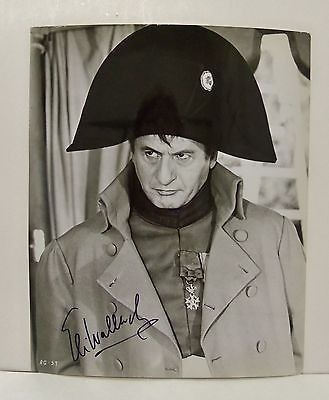

Eli Wallach in the 1970 movie The Adventures of Gerard that Adrian Conan Doyle was a part of

Eli Wallach in the 1970 movie The Adventures of Gerard that Adrian Conan Doyle was a part of

The great French-American historian and literary critic, Jacques Barzun, once wrote about the French painter Horace Vernet’s “Napoleonic scenes, which so captivated that Emperor-worshipper, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.”

When questioned about the source for his assertion, Barzun advised me that it was simply based on combining Conan Doyle’s well-known admiration for Napoleon with his giving a Vernet family connection to Sherlock Holmes himself in the story “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter.”

But did Conan Doyle idolize or worship Napoleon? Nothing in his writings, even the Brigadier Gerard stories, suggests that. In an 1894 interview in McClure’s Magazine, Conan Doyle told Canadian journalist Robert Barr that: “[Napoleon] was a wonderful man -- perhaps the most wonderful man who ever lived. What strikes me is the lack of finality in his character. When you make up your mind that he is a complete villain, you come on some noble trait, and then your admiration of this is lost in some act of incredible meanness. . . . Then, there must have been a great personal charm about the man, for some of those intimate with him loved him.”

And in his 1901 Preface to the Author’s Edition of his works, Conan Doyle wrote: “The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard . . . contains an impression of [Napoleon]. I am well aware that the portrait is very much too large for its frame: but, at least, it is a true portrait so far as it goes. . . . If the effect is inconclusive and natural, I may excuse myself by saying that after studying all the evidence which was available I was still unable to determine whether I was dealing with a great hero or with a great scoundrel. Of the adjective only could I be sure.”

Conan Doyle wrote extensively about the Napoleonic era — in chronological order, A Straggler of ’15, Waterloo, The Great Shadow, A Foreign Office Romance, Rodney Stone, Exploits of Gerard, Uncle Bernac, Adventures of Gerard, Through the Magic Door, “The Marriage of the Brigadier,” “The End of Devil Hawker,” “Lord Barrymore,” and “Slapping Sal.” This output covered a period of eighteen years — one-quarter of his life, though the bulk of it was crowded into the years 1891-1897.

Napoleon is referred to frequently in this work, although there are only a few occasions when he occupies centre-stage. Of the eighteen Brigadier Gerard stories, he is a prominent character in only three: How the Brigadier Slew the Brothers of Ajaccio, How the Brigadier Was Tempted by the Devil, and How the Brigadier Won his Medal. Napoleon is most prominent in the additional chapters of Uncle Bernac, which Conan Doyle wrote to pad the nine weekly instalments out to novel-length. Napoleon also has a role in the Brigadier Gerard play that Conan Doyle created out of his short stories in 1906, which later served as the basis for several film adaptations.

The Napoleon he portrays fictionally is an affectionate, irascible, and somewhat socially bumbling pater familias, rather than malevolent. This reflects his source, the Memoirs of Constant, sub-titled First Valet De Chambre of the Emperor, on the Private Life of Napoleon, His Family and His Court, which Conan Doyle, in his book about books Through the Magic Door (1907), describes as “written from that point of view in which it is proverbial that no man is a hero [to his valet].” This approach is a literary necessity, because Napoleon had to inspire the love and respect of his soldiers. A cruel, vindictive Napoleon would simply not make sense in Uncle Bernac, let alone in the Brigadier Gerard stories themselves.

Conan Doyle does give a darker view of Napoleon in that same wonderful book of literary criticism of his, commenting on Hippolyte Taine’s view in Les Origines de la France Contemporaine: “It is a wonderful figure of which you are conscious in the end, the figure of an archangel, but surely of an archangel of darkness.”

We will, after Taine’s method, take one fact and let it speak for itself. Napoleon left a legacy in a codicil to his will to a man who tried to assassinate Wellington. . . . You can whitewash him as you may, but you will never get a layer thick enough to cover the stain of that coldblooded deliberate endorsement of his noble adversary’s assassination. . . . This was the same man who had a royal duke shot in a ditch [the Duc d’Enghien] because he was a danger to his throne. Was he not himself a danger to every throne in Europe?

This equivocal comment surely is a far cry from hero-worship.

--

Clifford S. Goldfarb is a longtime member and former leader of The Bootmakers of Toronto, Canada’s senior Sherlock Holmes society, and the chairman of The Friends of the Arthur Conan Doyle Collection, supporting the Toronto Public Library. He is a lawyer, the author of the principal scholarly work about Sir Arthur’s Napoleonic tales, The Great Shadow (1996), and co-author with fellow lawyer and Bootmaker Hartley Nathan of Investigating Sherlock Holmes: Solved and Unsolved Mysteries (2014).