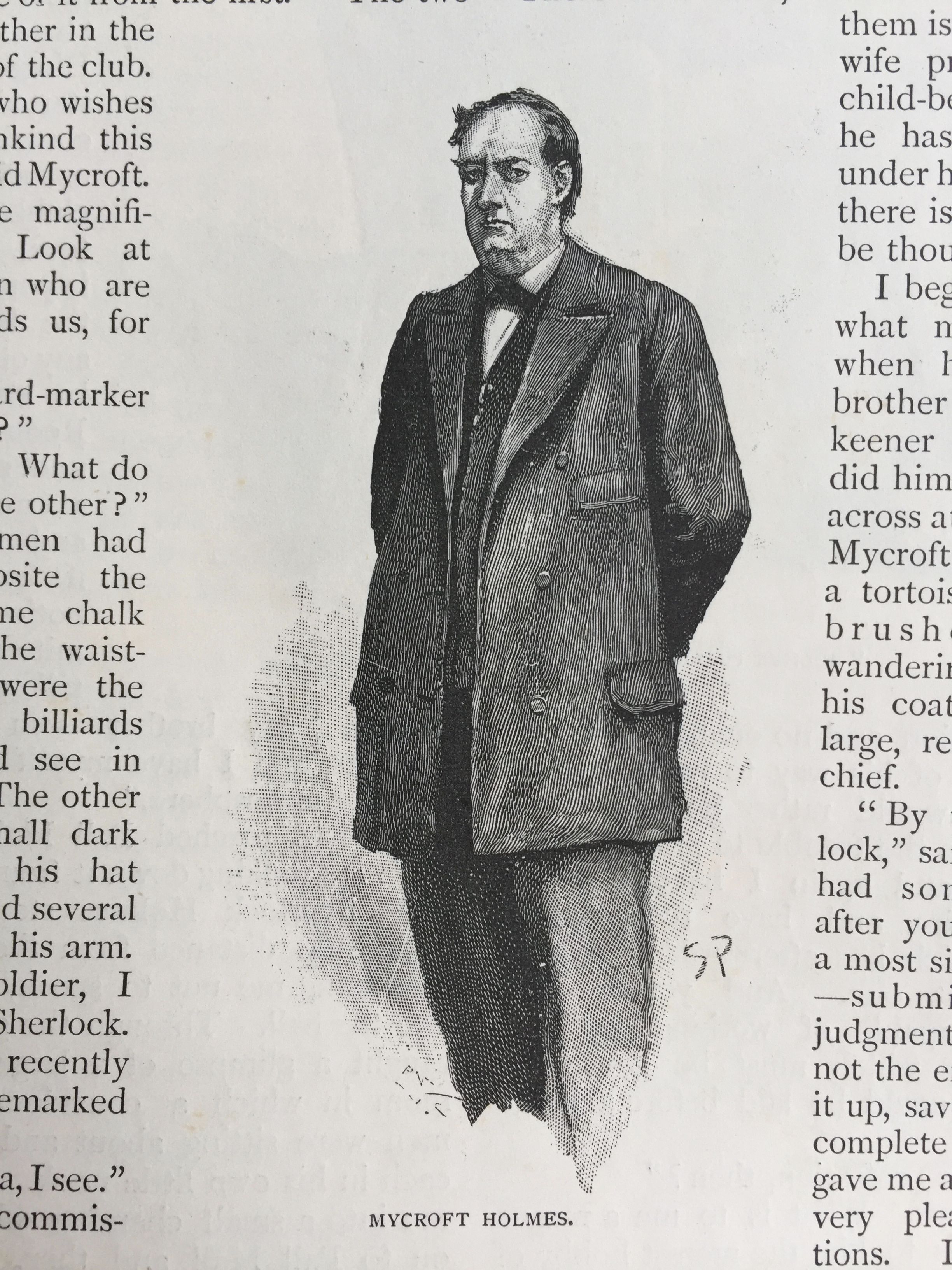

Sidney Paget's Mycroft Holmes in The Strand Magazine, 1893

Sidney Paget's Mycroft Holmes in The Strand Magazine, 1893

Robert Morley in A Study in Terror, with John Neville as Sherlock Holmes and Donald Houston as Dr. Watson

Robert Morley in A Study in Terror, with John Neville as Sherlock Holmes and Donald Houston as Dr. Watson

Charles Gray as Mycroft with Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes

Charles Gray as Mycroft with Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes

Heavily built and massive, there was a suggestion of uncouth physical inertia in the figure, but above this unwieldy frame there was perched a head so masterful in its brow, so alert in its steel-grey, deep-set eyes, so firm in its lips, and so subtle in its play of expression, that after the first glance one forgot the gross body and remembered only the dominant mind.

One of Arthur Conan Doyle’s more enigmatic characters is Mycroft Holmes, the older and smarter brother of the famous detective. We first encounter this Mr. Holmes in “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter,” where Sherlock Holmes tells Dr. Watson that not only does he have a brother, but one whose facility for deductive reasoning is superior to his own! We finally meet Mycroft at the Diogenes Club, and I must confess feeling that he may well be the most intriguing character in the entire Canon.

Canonically speaking, we know little about Mycroft. He is seven years Sherlock’s senior. (Tradition also suggests there may have been a third brother, the oldest—Sherrinford —who inherited the family estate in Yorkshire and lives the quiet life of a country squire; it’s difficult to imagine either Mycroft or Sherlock being fulfilled in such a prosaic existence.) We also know that their maternal grandmother was the sister of the celebrated French artist Vernet. “Art in the blood,” says Sherlock says, “is liable to the strangest forms”: and it certainly took a unique form in Mycroft, described as having an extraordinary faculty for figures and auditing the books in some government departments. Working in Whitehall, Mycroft lodges in Pall Mall across the street from the Diogenes Club, “the queerest club in London,” which he helped found—all within a very tight radius, with Mycroft seldom seen outside his fixed orbit.

Physically, Mycroft resembles his younger brother, but is “a much larger and stouter man.” When we meet him again in November 1895, in “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans,” a more fulsome description is given: “Heavily built and massive, there was a suggestion of uncouth physical inertia in the figure, but above this unwieldy frame there was perched a head so masterful in its brow, so alert in its steel-grey, deep-set eyes, so firm in its lips, and so subtle in its play of expression, that after the first glance one forgot the gross body and remembered only the dominant mind.”

In that story, we learn the truth about Mycroft—that occasionally he is the British Government! Like Sherlock, Mycroft has created a completely unique career for himself, credited with being “the most indispensable man in the country.”

“He has the tidiest and most orderly brain, with the greatest capacity for storing facts, of any man living. The same great powers which I have turned to the detection of crime he has used for this particular business. The conclusions of every department are passed to him, and he is the central exchange, the clearinghouse, which makes out the balance. All other men are specialists, but his specialism is omniscience. We will suppose that a minister needs information as to a point which involves the Navy, India, Canada and the bimetallic question; he could get his separate advices from various departments upon each, but only Mycroft can focus them all, and say offhand how each factor would affect the other. They began by using him as a short-cut, a convenience; now he has made himself an essential. In that great brain of his everything is pigeon-holed and can be handed out in an instant.”

That’s about the extent of what we know about Mycroft, but where data ends, deduction begins, and there is much to deduce about the secretive Mycroft Holmes. He has made more appearances in pastiches and movie and television adaptations than I care to mention, some better than others. Among the better portrayals one would do well to read Enter the Lion (1979) by Michael Hodel and Sean Wright, introducing us to a younger, more active Mycroft, newly employed by Her Majesty’s Government in the late 1870s. In movies, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better, more thoroughly canonical Mycroft than Robert Morley’s portrayal in A Study in Terror (1965). I also quite enjoy Charles Gray in both The Seven Per-Cent Solution (1976) and the Granada television series opposite Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock Holmes. Stephen Fry is also a faithful Mycroft (aside from the disturbingly funny but not quite canonical “clothing optional” Diogenes Club) in Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011). And all these screen Mycrofts posit him as an early pioneer of the British Secret Service. (None more so than Christopher Lee’s brilliant but decidedly non-canonical Mycroft in Billy Wilder’s Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in 1970.) As a naval intelligence officer, currently serving my fourth tour at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., I’m attracted to the idea. But can we attribute this popular interpretation of Mycroft’s government service to anything intended by his creator?

During the fifteen or so years between when Conan Doyle wrote “The Greek Interpreter” and “The Bruce-Partington Plans,” he was in fact introduced to British intelligence work in Cairo in the winter of 1895-96. By mid-1900, he’d become increasingly interested in military and naval reform following service as a volunteer army field surgeon in South Africa during the Boer War. By 1908, the year “The Bruce-Partington Plans” was published, he and several other well-known authors of the time were deeply concerned about British national security and defense. Doyle had become quite a navalist, corresponding with senior Admiralty leaders including the First Sea Lord, Admiral John “Jacky” Fisher. In addition to giving Mycroft purview over the nascent and secret Bruce-Partington submarine, Doyle also wrote other stories highlighting emerging threats, including a fictional account of an imaginary European power defeating Britain with submarines. “Danger! Being the Log of Captain John Sirius,” came out in TheStrand Magazine in July 1914, barely a month before the World War broke out.

Mycroft Holmes is only mentioned in four stories, “The Greek Interpreter,” “The Bruce-Partington Plans,” “The Final Problem” and “The Empty House,” but he made an enormous impression on the literary world. I like to think it was Mycroft who served as Ian Fleming’s inspiration for the surly and mysterious “M,” chief of the British Secret Service (MI6). Mycroft has his Diogenes Club, and “M” his Blades, a fictional gentlemen’s club featured in the 007 spy thrillers, most notably Moonraker.

--

Written by Michael J. Quigley, a Naval intelligence officer serving in the Office of the Secretary of Defence at the Pentagon, is a member of the Baker Street Irregulars, and the founder and Gasogene of The Diogenes Club of Washington, D.C., devoted to the study of the Sherlock Holmes stories’ national security elements.