Patrick Forbes, Conan Doyle's model for the dashing adventurer Lord Roxton

Patrick Forbes, Conan Doyle's model for the dashing adventurer Lord Roxton

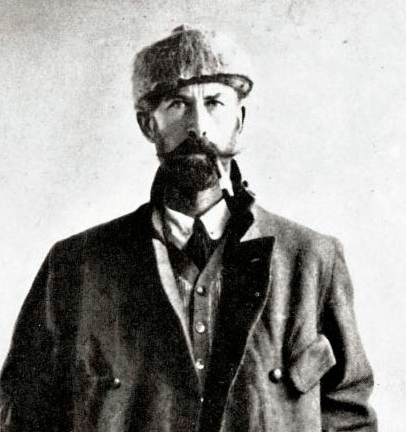

Percy Fawcett - one of the several historical figures who have been suggested as a model for Roxton

Percy Fawcett - one of the several historical figures who have been suggested as a model for Roxton

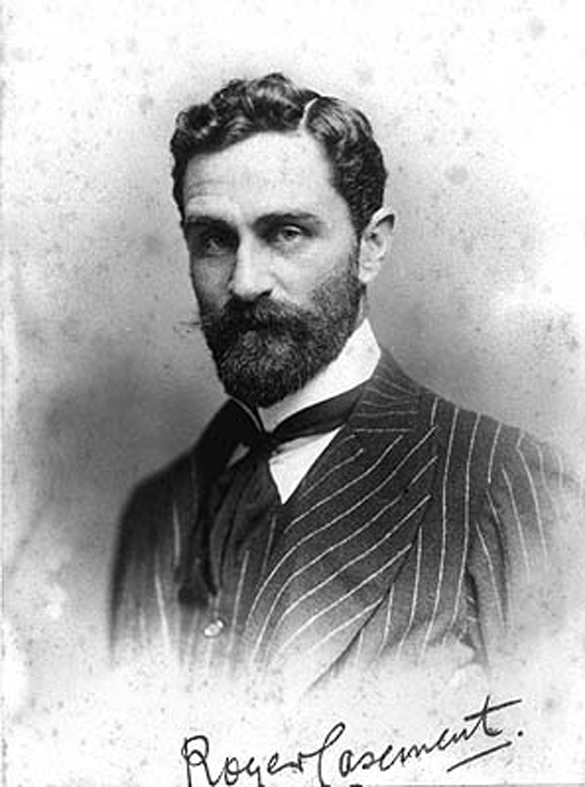

Roger Casement, the other historical figure Conan Doyle modelled Lord Roxton on

Roger Casement, the other historical figure Conan Doyle modelled Lord Roxton on

Lewis Stone in 1925

Lewis Stone in 1925

Michael Rennie in 1960

Michael Rennie in 1960

An Oxford alumnus and member of the renowned Oxfordshire-based Leander rowing club, Roxton’s “reputation as a sportsman and a traveller is, of course, world famous.” He is familiar with the countryside and language of central South America, and does not hesitate to volunteer for Professor Challenger’s dangerous foray into the uncharted rainforest.

Big game hunter, mountaineer, explorer, sportsman (golf, fencing, boxing, rowing)—Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lord John Roxton is the perfect type of the Edwardian all-round outdoorsman and adventurer.He appears in the three Professor Challenger novels: The Lost World (1912), The Poison Belt (1913), and The Land of Mist (1926).

Conan Doyle describes him as tall, thin and ruddy-faced with rounded shoulders, yet “strongly built,” dark gingery thinning hair, a strongly curved nose, hollow cheeks and icy blue eyes. He affects “crisp, virile moustaches” with a “small, aggressive tuft upon his projecting chin.” “His eyebrows are tufted and overhanging, which gave those naturally cold eyes an almost ferocious aspect, an impression which was increased by his strong and furrowed brow”— exceedingly neat and prim in his ways, dresses always with great care in white drill suits and high brown mosquito boots, and shaves at least once a day. Like most men of action, he is laconic in speech, and sinks readily into his own thoughts, but he is always quick to answer a question or join in a conversation, talking in a queer, jerky, half-humorous fashion.

We get some idea of how Conan Doyle intended Roxton to look from his “photograph” in the first print edition of The Lost World. In a clever practical joke on readers, the author carefully set up the picture with himself as Challenger, and used his brother-in-law Patrick Forbes in disguise as well as his model for the dashing adventurer.

An Oxford alumnus and member of the renowned Oxfordshire-based Leander rowing club, Roxton’s “reputation as a sportsman and a traveller is, of course, world famous.” He is familiar with the countryside and language of central South America, and does not hesitate to volunteer for Professor Challenger’s dangerous foray into the uncharted rainforest: “A sportin’ risk,” he declares, is “the salt of existence.” But the adventure addict is not without his nobler side as well. A passionate anti-slaver, Roxton describes himself as “the flail of the Lord,” bringing his rifle to bear against slavers in Peru. “There are times, young fellah, when every one of us must make a stand for human right and justice, or you never feel clean again.”

Roxton is variously referred to as “Lord John Roxton,” “Lord John” and “Lord Roxton.” The first two forms are courtesy titles: Roxton, as third son of the Duke of Pomfret, would be permitted to use the title “Lord” though not himself a member of the peerage. (“Lord Roxton” is probably incorrect usage: (title) + (surname) is reserved for noblemen, and there’s no evidence that he is one of these.) In any case, it’s clear that he comes from privilege: lacking any apparent remunerative profession, he can nonetheless put his hands on enough resources to support his frequent global adventures.

He is a principal player in The Lost World, charging in to rescue his companions on a number of occasions, and dealing expertly with prehistoric creatures and hostile natives. In contrast, Roxton is given very little to do in The Poison Belt; his chief applicable skill is his ability to drive a twenty-horsepower Humber—though no small feat at a time when every automobile was operated differently.

In The Land of Mist Roxton’s physical prowess is back in demand, but the questions of belief, spiritualism and science raised by the novel seem beyond him. Though he expresses interest in spiritualism at the beginning of the story, he stays in character as an adventurer, rarely expressing himself more eloquently than “Oh, I say! By Jove! What!” As the story wraps up, the narrator reports that Roxton “had become assiduous in his psychic studies, and was rapidly progressing in knowledge," but the man himself never hints that he may have been converted to the new religion.

Several historical figures have been suggested as models for Roxton. The most likely are Roger Casement and Percy Harrison Fawcett. Both were also tall with athletic physiques and grey eyes, and known to Conan Doyle. Casement was a British diplomat who investigated and exposed the abuse of indigenous peoples in the Congo and Peru, much as Roxton did in South America. (Conan Doyle himself did much to raise awareness of such horrors in The Crime of the Congo in 1906, citing Casement extensively.) Fawcett, whom Conan Doyle heard speak in early 1911 as he began writing The Lost World, was a British Army officer who led seven expeditions to the heart of South America between 1906 and 1924, earning respect from its indigenous peoples through gifts, patience, and a respectful approach.

Lord John Roxton has been played by actors ranging from, in 1925, the dignified Lewis Stone, to the dashing if clean-shaven Michael Rennie in 1960, and by portrayals in between in many other movie, television, and audio dramatizations of The Lost World, one of the world’s greatest early examples of science-fiction adventure. In them all, the character of Lord John Roxton vividly demonstrated Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s regard for the dashing adventurer, a man with, like Conan Doyle himself, a strong moral sense and a zest to discover the unknown.

--

Written by Doug Elliott, a long-time Baker Street Irregular and Doylean born in Canada, is a founding member of The Friends of the Arthur Conan Doyle Collection of the Toronto Public Library. He has authored The Curious Incident of the Missing Link: Arthur Conan Doyle and Piltdown Man and the related historical thriller The Link, and co-edited The Annotated White Company about Conan Doyle’s own greatest historical novel. He lives in Sydney, Australia, where he co-edited Sherlock Holmes and Australia as well.