An American-born opera singer with a European renown, Irene Adler is described as “having a face a man might die for” and being “the daintiest thing under a bonnet on this planet.”

In “The Adventure of the Five Orange Pips,” Sherlock Holmes admits that “I have been beaten four times — three times by men, and once by a woman.” Who was his formidable female adversary? Irene Adler, a well-known adventuress of dubious and questionable memory, who appears only in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” but her influence extends well beyond a single tale.

An American-born opera singer with a European renown, Irene Adler is described as “having a face a man might die for” and being “the daintiest thing under a bonnet on this planet,” yet Sir Arthur Conan Doyle never fully fleshes out her physical appearance. It is her character instead that stamps itself indelibly on the minds of those who encounter her in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” and the story’s readers. Her former lover, who comes to Holmes for help, is Wilhelm Gottsreich Sigismond von Ormstein, Grand Duke of Cassel-Felstein and hereditary King of Bohemia. While he is quick to praise her “beautiful face,” he also acclaims her independent spirit: “She has the mind of the most resolute of men…a soul of steel.” Adler had nerves to match: she had foiled no fewer than five attempts of his, two of them involving physical attack, to retrieve the damning photograph of them that she planned to send to his royal fiancée to break off their impending marriage.

Holmes also comes to admire ruefully her courage and resourcefulness after she figures out his smoke-bomb hoax in an attempt of his own, in disguise, to recover the photograph, afterwards trailing him back to Baker Street in disguise herself, taunting him at his own front door, and quickly leaving London forever with her new husband and the photograph, which she promises to never use against the man who jilted her. The King acknowledges that “her word is inviolate,” remarking that it is a pity Adler was not born on his level. Holmes, who by now has seen enough of them both, replies: “From what I have seen of the lady, she seems, indeed, to be on a very different level to Your Majesty.”

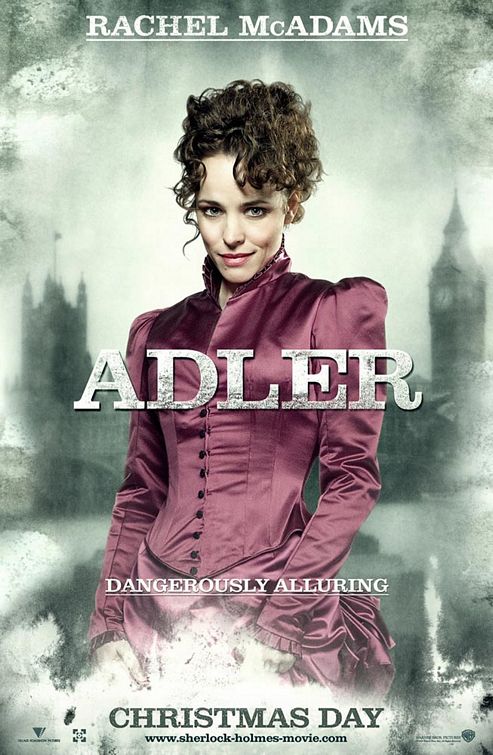

Sherlock Holmes prides himself on being “the most perfect reasoning and observing machine,” his intellect dedicated to the pursuit of justice and good. Professor James Moriarty is his diametric opposite, a criminal genius who applies his superior mental powers to evil ends. Irene Adler also embodies an opposition of equals, but a different one based on her gender, not her moral compass. She is not like the blushing maiden whom Dr. Watson marries, nor Holmes’s typical distraught female clients, nor even one of the scheming, manipulative femmes fatales of the Canon, such as Isadora Klein in “The Adventure of the Three Gables” or Maria Pinto in “The Problem of Thor Bridge.” In motion pictures Irene Adler has been portrayed as an equally strong woman, including performances by Charlotte Rampling in Sherlock Holmes in New York (1976), Morgan Fairchild in Sherlock Holmes and the Leading Lady (1992), and Rachel McAdams in the two Warner Bros. movies to date, Sherlock Holmes (2009) and The Game of Shadows (2011).

And so, for Holmes, Irene Adler is always “the woman…she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.” He admits that she bested him fair and square, and uses this honorable title to distinguish her from the ladies, lasses, and damsels in distress with whom he will interact throughout his career.

Arthur Conan Doyle made a daring choice to present such a strong female character and adversary as facing, and besting, Sherlock Holmes in the very first short story in 1891 featuring his not yet well-established character. Irene Adler rises above the norm of most female literary characters of the time, and does it with grace, guts, and wit. By showing that Holmes was fallible, Conan Doyle gave this still nascent creation another facet to his personality, rendering him more fully as a human being who lives both on the printed page and in our imaginations.

--

Written by Katherine Karlson, “The Evening Standard” in the Baker Street Irregulars and “Kitty Winter” in The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes, discovered Sherlock Holmes a half century ago. Her active career includes regular contributions to various scholarly publications and presentations to literary societies from Toronto to Sydney. In 2007, with Patricia Guy, she co-edited Ladies, Ladies: The Women in the Life of Sherlock Holmes. She lives in Binghamton, N.Y. with her long-suffering spouse Edward L. Ware.